Table of Contents

Date: SUN 7:00pm 22nd February 2026

Preacher: Rev. David McMillan

Bible Reference: Psalm 66:16

Podcast

Testimony of David McMillan

Psalm 115:1 sets a tone that defines the authentic Christian life: “Not unto us, O Lord, not unto us, but unto thy name give glory, for thy mercy, and for thy truth’s sake.” That text, read at the outset of a sermon, establishes the right framework for reflection — not one of self-exaltation or personal achievement, but humble acknowledgment that all things, both the triumphs and the trials, serve the glory of God. Every phase of a believer’s life, from conversion to calling, from affliction to restoration, unfolds under His providential hand.

What follows is a detailed account drawn from the life and testimony of a faithful minister, one whose journey from a rural County Down upbringing to a lifetime of Gospel service bears the unmistakable imprint of divine mercy. It is a story deeply entwined with the theology of grace, the simplicity of Presbyterian faith, and the conviction that “the Lord hath kept me alive.”

Early Life: Religious Yet Unsaved

The preacher was born in November 1965 in Newtownards and reared between Carryduff and Saintfield on the Oakley Hill, a high rural ridge overlooking the County Down countryside. His family was active in First Saintfield Presbyterian Church—faithful in attendance, dutiful in service, and moral in conduct. Yet for all their religious activity, there was no saving knowledge of Christ in the home. He admitted that, though the family rarely missed a meeting, he never once heard a clear Gospel message in his youth.

This portrayal of spiritual blindness within formal religion is not unique in Ulster’s story. Entire generations were brought up under church roofs, surrounded by sermons, hymns, committees, and rituals, yet untouched by the regenerating power of the Gospel. He would later reflect that this institutional religiosity — moral but unconverted — is more perilous than open vice, because it gives the illusion of righteousness without the reality.

The Providence of a Schoolhouse

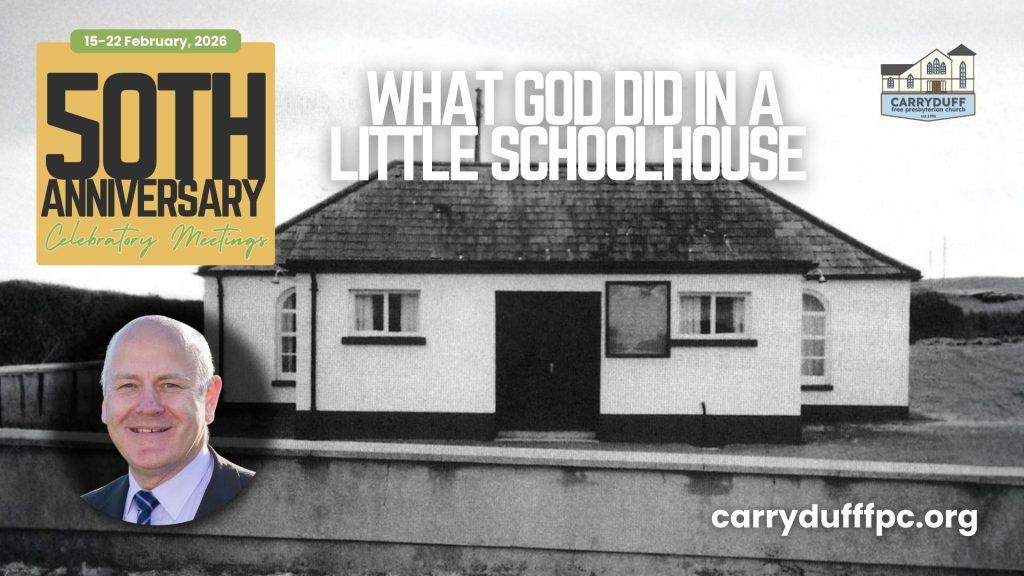

The turning point came through the vision of a layman, Mr Robert Lowe, a farmer from Killingay, who longed to see a Gospel witness in his district. The old Killaney Schoolhouse, boarded-up and abandoned after years of neglect, stood as a silent relic on the roadside. Lowe and Dr Ian Paisley, then minister of Martyrs Memorial Church in Belfast, saw in that dilapidated building an opportunity for evangelisation.

Their partnership led to its reopening as a mission hall — a testimony not only to zeal but to the Protestant spirit of independent Gospel endeavour that marks the Free Presbyterian tradition. Men like Lowe are often overlooked by history, yet their influence is immeasurable; they do the hidden groundwork of revival. It was in that little hall that the young boy first heard the Gospel preached clearly — the message that man is lost, Christ is a perfect Saviour, and salvation is by grace through faith alone.

One Sunday afternoon in January 1979, at the age of thirteen, he attended a meeting where Dr Paisley himself preached. The message pierced his conscience. At the close of the meeting, he and his elder brother stepped into a small back room barely seven feet square, where he knelt with Paisley and Lowe. There, guided through the Scriptures — the “Roman Road” of salvation — he confessed his sin and trusted Christ. His memory of Paisley, looking over his half-moon glasses and holding an open Bible, remained vivid for decades.

That humble room became sacred ground to him, “redemption ground,” as he called it. Whenever he later visited the building, he would open the door and glance inside to recall where the transaction of grace had taken place. Christianity for him was not a ritual or declaration; it was an encounter.

Growth Amid Simplicity

His conversion did not occur in isolation; the Free Presbyterian community quickly drew around him. The evening meetings in Killaney provided not only ministry but mentorship. The zealous evangelism, the plain preaching of Scripture, and the genuine fellowship stood in stark contrast to the comfortable formalism of mainstream ecclesiastical life.

He joined the Martyrs Memorial Free Presbyterian Church, led by Dr Paisley. It was there, at seventeen, that he took communicant membership. In those days, admission meant serious scrutiny and spiritual preparation. He recounted that when he sought to join merely as a “congregational member,” Dr Paisley struck out the option and told him, “You want to be a communicant member.” That seemingly simple redirection set a chain of providence in motion. It ensured he met the later qualifications for entering theological training — something he had not even imagined at the time.

Labour on the Land, and Lessons From Providence

Farming was his first love. He trained at Loughry Agricultural College in Cookstown, earning his agricultural certificates and intending to spend his life among dairy cattle. He described farming not as labour but as joy — a lifestyle that brought him satisfaction and purpose.

Yet, God disrupted his plans. When the milk quota system was introduced across the UK and Ireland in the 1980s, his family’s plans to establish a dairy herd were halted. The tribunal that assessed their appeal ruled they had not “spent enough” to qualify. Initially bitterly disappointed, he later saw this as the Lord’s deliberate hand closing the door on a false future. “Had we invested the money, I might never have left the farm for the ministry,” he later said, with gratitude rather than regret.

This theme recurred throughout his testimony — the belief that divine providence is often disguised as disappointment. The closed door, the failed exam, the interrupted plan — all of them form part of a divine reversal that reveals its beauty only in hindsight.

The Call to the Gospel Ministry

The call to Christian ministry came quietly but irresistibly. One night at a meeting in Mount Merrion Free Presbyterian Church, Dr Alan Cairns preached and shared his own testimony of calling. The young farmer listened, convicted. The notion that God could call an ordinary country lad to preach seemed impossible, yet undeniable.

Still, he resisted that call for nearly two years — a struggle typical of those whom God intends to humble before He uses them. But one Sabbath afternoon, while reading Luke chapter 1, he came upon the verse concerning John the Baptist: “Thy child shall be called the prophet of the Highest.” It broke through every defense. He knelt beside his bed, surrendered entirely to God’s will, and committed himself to the ministry. From that moment, the certainty of his calling never wavered.

Academic Preparation and Early Humbling

To enter training at the Whitfield College of the Bible, he needed three O-levels. He had none. He took night classes in Castle Ray College — English Language, English Literature, and History. He failed English twice. Ironically, his future ministry would require him to write thousands of words weekly.

Under teachers like Dr John Douglas, he learned discipline. Douglas and Dr Ian R. K. Paisley both believed that a preacher ought to master his language. Douglas was known to stop a lecturer mid-sentence for a misused word. They drilled grammar, pronunciation, and communication as spiritual tools. Through relentless effort, the once-failing student became an eloquent preacher and writer. Over twenty-five years later, he wrote columns in The Belfast Newsletter, The Farming Life, and other publications with a readership exceeding 100,000. Columns like Paper Pulpit and Weekly Wisdom brought Scripture into the public square — in nationalist districts, rural communities, and even foreign translations. His articles were circulated globally and used by churches in Lebanon and the Middle East, translated into Arabic.

He often marvelled: “For a fella that couldn’t pass English twice — isn’t it amazing what the Lord can do?”

Ministry Across the Isles

After completing theological training in 1991, he began his pastoral work in West Wales, serving the small Free Presbyterian congregation in Bury Port. Ministry in Wales demanded perseverance. Congregations were small; communities cautious of Northern Irish Protestantism. Yet through those years, preaching and visitation produced fruit. Dr Paisley later travelled to open the newly built church and commended him to the presbytery for ordination.

Ordained in the Tandragee Free Presbyterian Church — his wife’s home congregation — he served in Bury Port for nine years, then in Mullaglass, County Armagh, for another nine, and finally in Armagh city itself, known as Ireland’s “ecclesiastical capital.” There he preached in a landscape dominated by religious symbolism but impoverished in Gospel truth. “A very religious city,” he called it, “and yet so many are sincerely religious and sincerely wrong.”

In each pastorate he showed uncommon humility: he saw himself as only a servant. He never forgot his rural background, which gave his preaching plainness and warmth. Many of his texts were drawn from the Psalms and agricultural parables, an echo of Christ’s own use of fields, flocks, and seed to portray spiritual truths.

The Long Shadow of Bereavement

His college years were marked by tragedy. In 1988 — within a span of months — his father, uncle, and seventeen-year-old brother all died. His father, aged fifty-eight, succumbed suddenly, and his younger brother Gordon, born with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, followed later that year. Such losses could have derailed a weaker soul. Instead, they forged in him a deeper understanding of brevity and eternity.

He testified: “Some suggested I had made a mistake and should return home to look after the farm. But I knew that if ever I was going to do work for God, I must do it then — for life is short.” The lesson, hardened through grief, became the axis of his ministry: urgency in evangelism and diligence in service.

Marriage and Companionship in Service

At Whitfield College, he met his future wife, Roberta, who had served as deputy matron before entering theological studies herself. Their courtship was unassuming but devoted. In keeping with Free Presbyterian custom, he sought presbytery permission to marry — even undergoing a sessional interview with Dr Douglas, who reminded him of the centrality of study before sentiment.

The couple were married between his second and third year of studies, honeymooned through rural Ireland and then assisted in a summer mission in Wales. Their life together manifested the old principle that a minister’s wife is not a passive bystander but a co-labourer — hospitality, women’s work, and prayer forming her unseen pulpit.

The Sovereign Mercy of Survival

One of the defining moments in his life came decades later, on 23 April 2018. Preparing for missionary travel to Uganda, he collapsed suddenly in Dublin Airport, struck by cardiac arrest. Statistically, survival from such an event outside hospital is about eight per cent. Providence, once again, wrote another chapter.

A passing nurse, his companion Mr Alistair Hamilton, and an airport police officer trained in first aid all converged within seconds. The airport’s defibrillator programme, established years earlier after a fatal incident, ensured the necessary equipment was immediately available. Paramedics arrived moments later and rushed him to Dublin’s Mater Hospital.

Doctors discovered a 95% blockage in the main left coronary artery — the “widow-maker.” Within hours, a double bypass was performed by the hospital’s leading cardiac surgeon, who postponed his own holiday to carry out the procedure. When the preacher awoke, alive and stable, he understood the magnitude of what had occurred: “The Lord has kept me alive,” he said, echoing Joshua 14:10.

The episode left not anxiety but renewed gratitude. He testified that he bore no fear of death, for the Lord who held his heart in the theatre was the same Shepherd who had saved him at thirteen on that January night in Killaney.

From the Psalm to the Shepherd

His preaching often turned from biography to theology, culminating in an exposition of Psalm 23 — a text so universally known that its familiarity often conceals its depth. He used a story frequently circulated among evangelicals: an actor and an aged minister reciting the psalm. The actor’s version inspired applause; the minister’s evoked tears. The actor concluded, “I know the psalm, but he knows the Shepherd.”

He declared that every listener faces that same question: “You know the psalm — but do you know the Shepherd?” The psalm outlines three incomparable assurances for those who can answer “Yes.”

- Provision in Life:

“I shall not want.” The believer’s security is not in abundance but sufficiency. The Lord, as Jehovah-Jireh, provides every material and spiritual need. - Peace in Death:

“Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.” The shadow implies presence — death looms, but Christ removes its substance. The Christian walks through the valley, not into it, for beyond lies light. - Promise for Eternity:

“Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” Eternal rest is not earned but bestowed upon those who know the Shepherd personally.

He underscored that religion, tradition, and knowledge are no substitute for relationship. Only a personal confession — “The Lord is my Shepherd” — gives peace in life, death, and eternity.

The Pressing Question of Eternity

In closing, he invited solemn reflection: Why am I spared when others are taken? If unsaved, one is spared to repent. If saved, one is spared to serve. Eternity, he reminded, is not a distant abstraction but the most immediate reality. “The things which are seen are temporal,” he quoted from Corinthians, “but the things which are unseen are eternal.”

Citing Dr John (“Rabbi”) Duncan, the Scottish missionary-scholar, he ended with the simple greeting that carried more weight than a dozen sermons: “A happy eternity, gentlemen.” For what profit is there in a happy year, a successful career, a long life, if eternity is misery?

The challenge was clear and inescapable: Do you know the Shepherd? If so, you can rest in His promise; if not, seek Him now.

Final Reflection

Looking back across six decades, the minister recognised a coherent pattern only visible from hindsight. His life was an unbroken chain of providence: a shut schoolhouse reopened; a farm career derailed; exams failed then passed; a heart stopped then restarted. Each link testified to the sovereignty of grace.

His closing words captured the essence of that faith:

“Through many dangers, toils, and snares, I have already come; ’tis grace hath brought me safe thus far, and grace will lead me home.”

It is an old hymn, yes — but for him, it was biography set to verse.