🌍 Introduction — When Doctrine Walked the Streets

In June 1966 Belfast became a stage upon which theology, not politics, took centre place. The pounding of hymn tunes on cobblestones echoed further than the city understood. For the small Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster, only fifteen years old, the March of Witness organised under the banner of Rev. Dr. Ian Paisley was intended to proclaim Christ as Redeemer and to warn against creeping compromise within Irish Protestantism.

To many journalists it looked like old sectarian thunder. To those marching, it was something altogether purer — a procession shaped by conscience, not by culture. Their authority was Scripture, their foundation the Westminster Confession of Faith, which declares:

“The Supreme Judge, by which all controversies of religion are to be determined, can be no other but the Holy Spirit speaking in the Scripture.” (WCF 1.10)

The marchers believed that when hearts cool toward that truth, Christianity ceases to be Christianity at all.

📜 Setting the Scene — From 1927’s Heresy Trial to a Nation’s Apathy

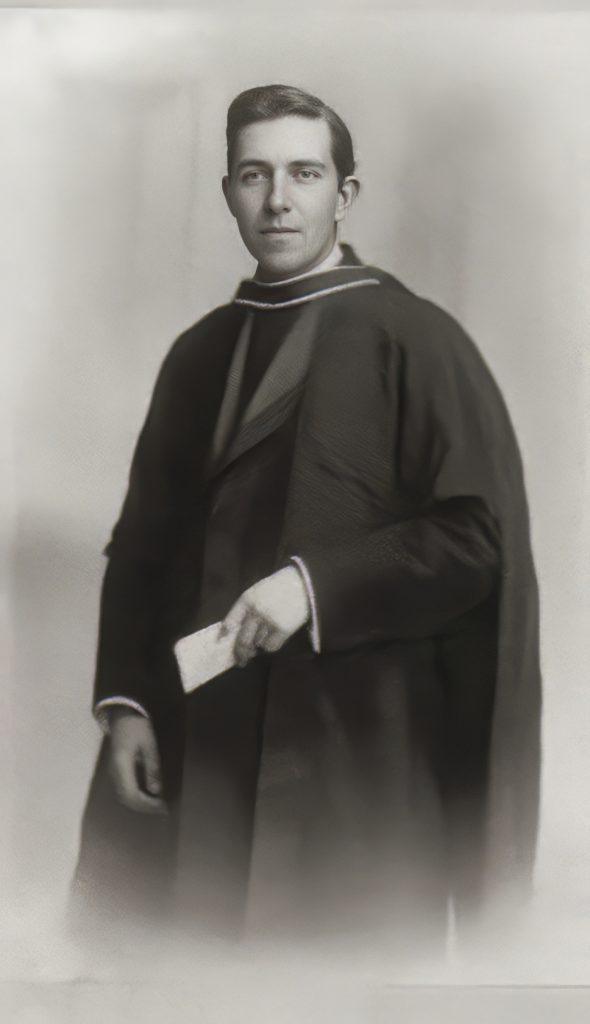

Nearly forty years before Cromac Square, the J. E. Davey Trial exposed the rift tearing at Irish Presbyterianism. The acquittal in 1927 of a professor who denied Christ’s virgin birth and the infallibility of Scripture signalled that intellectual modernism had captured the denomination’s highest pulpit.

By the 1960s, liberalism had matured into policy. The Presbyterian Church in Ireland (PCI) participated in the nascent World Council of Churches, entertained Roman Catholic clergy as official guests, and courted union with the Church of Ireland. For many ordinary members this merely sounded progressive. For convictional Calvinists it sounded apocalyptic.

The small Free Presbyterian Church, formed in 1951 after cross‑denominational missions were shut down by local presbyteries, had grown quietly in rural Ulster. It drew shop‑workers, farmers, and ex‑soldiers who missed the thunder of old Gospel preaching.

“A Time to Be Remembered” recounts that before 1966, the atmosphere in prayer meetings was thick with longing: “We prayed for revival, never dreaming our prayers would be answered in riot and imprisonment.”

🔥 6th June 1966 — The Ambush at Cromac Square

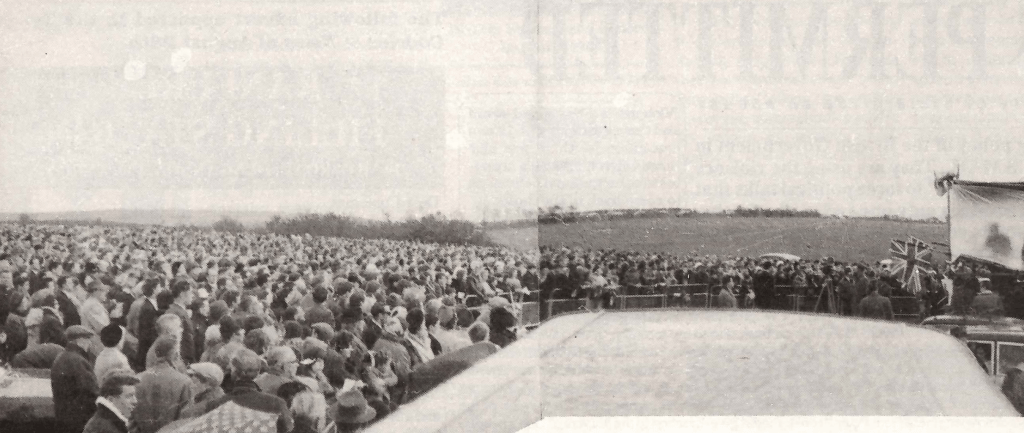

The March of Witness set out across the Albert Bridge at dusk. Hundreds carried Bibles or hymn‑books; bands played The Old Rugged Cross. They were to proceed through Cromac Square—a heavily nationalist area—en route to the General Assembly at May Street.

Unknown to them, republican youth groups had spent the weekend stockpiling broken masonry and railway bolts. When the head of the march reached the bridge’s decline, the first missiles flew.

“One middle‑aged woman, with bricks smashing at her feet, continued to sing ‘Onward Christian Soldiers.’” (Belfast Telegraph, 7 June 1966)

Head Constable Robert Finlay fell unconscious; four other police required hospitalisation alongside a 12‑year‑old child. Dozens of cars were wrecked and the post office windows shattered.

Yet eyewitness reports in both the secular press and The Burning Bush agreed: no Free Presbyterian retaliated. They simply sang louder.

Rev. W. Beattie later said, “When the bottles came, I thought of the covenanters singing on the moors.” That reference was deliberate; the marchers saw themselves walking in the line of Knox, Luther, and the Scottish Covenanters who had resisted kings rather than surrender conscience.

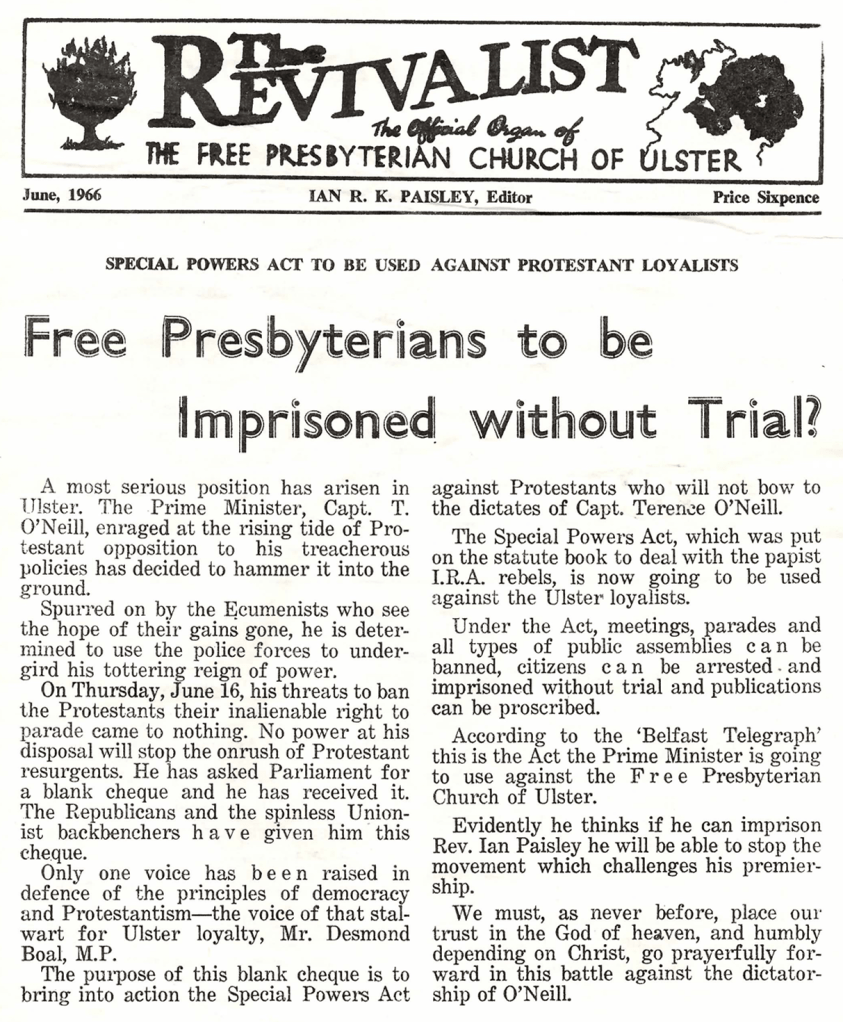

⚖️ Stormont’s Discomfort and Westminster’s Curiosity

The imagery of hymn‑singing congregants showered with debris embarrassed the Northern Ireland Government and drew questions at Westminster. When Home Secretary Roy Jenkins asked Prime Minister Terence O’Neill whether such parades should be banned, O’Neill replied diplomatically that “these are matters of judgment.”

Meanwhile The Times (London) ran an article asking, “Is Ulster religion merely a branch of politics?” Paisley’s rebuttal was swift:

“Our protest is not political. We stand for the Gospel where others now stand for expediency.”

This distinction mattered. Free Presbyterians rejected both extremes — the secular nationalism of the republicans and the complacent nominalism of establishment Protestantism. “The Burning Bush” summarised it precisely: “Our quarrel is not with Rome’s people, but with Rome’s doctrine, and with any church that forgets why the Reformers died.”

🕊️ Imprisoned for Obedience

After the 6th June 1966 Assembly protest, the RUC argued that the clergy’s march from Ravenhill Road through Cromac Square had been likely to endanger peace because tension already existed in the surrounding nationalist district. Paisley and his colleagues appeared before a magistrate at Belfast Petty Sessions. They were not accused of violence or incitement; rather, under Section 5, each was ordered to post a £500 recognisance guaranteeing future “good behaviour” for two years. The three ministers refused on principle, arguing that accepting the bond would imply guilt for disorder they had neither caused nor incited. Their refusal automatically triggered the penal clause: three months’ imprisonment in Crumlin Road Gaol.

Technically, the imprisonment of Paisley, Wylie, and Foster was lawful under the narrow reading of Section 5. Morally and constitutionally, it was indefensible. No allegation of violence was proven, no appeal permitted, and the peace‑bond mechanism—intended to restrain chronic brawlers—was used to silence political preachers. The legality stood; the justice faltered. What Stormont viewed as a tidy administrative containment became, in public eyes, the criminalisation of conscience—and thus the seed of the evangelical revival that followed.

From his iron‑barred study in Crumlin Road Gaol, Paisley wrote a series of meditations on the Pastoral Epistles, later published privately as Letters from a Prisoner of Conscience. One line became almost proverbial in Ulster pulpits:

“You can chain the preacher, but never the Word of God.” (2 Timothy 2:9)

Even prison officers admitted respect for their discipline. Warder McBride told a Belfast News Letter reporter that they were “the quietest and most courteous men we have ever had.”

Outside the prison walls each evening, hundreds stood in the rain singing psalms. Converts came simply from hearing the words echo through Clifton Street: “God is our refuge and our strength, a very present help in trouble.”

By the time the ministers emerged in August 1966, the movement had trebled in attendance. Ulster had awakened.

⛪ 1967 — The Year of Decision

The following June, as the PCI prepared new ecumenical overtures, Free Presbyterians felt compelled to bear witness again. A crowd of 600 gathered outside May Street Church House. Placards read “The Pope Is Not Christ’s Vicar But Man of Sin.” Banners quoted Galatians 1:8.

Paisley addressed them:

“Though tin trumpets may drown our song, the trumpet of Romans 1:17 still sounds—‘The just shall live by faith.’”

The Belfast Newsletter described the scene as “fierce yet strangely reverent.” This protest ended without riot but solidified identity: the Free Presbyterian Church was no longer a local oddity; it had become a movement with momentum.

📖 The Reformation Revived — Theology in the Streets

Observers unfamiliar with Reformed history missed the continuity. The Free Presbyterians consciously modelled themselves on earlier reformers who believed that truth is not private property but public trust.

John Knox had written that when the Gospel is endangered, “silence is neither love nor loyalty.” The Free Presbyterians quoted another line—Matthew 10:27: “What ye hear in the ear, that preach ye upon the housetops.”

The theology was stark: God demands separation from unbelief. WCF 20.2 summarises:

“God alone is Lord of the conscience, and hath left it free from the doctrines and commandments of men.”

In their eyes, the PCI had replaced apostolic authority with academic opinion. Therefore, to remain within it was impossible without sin. That conviction, more than Paisley’s personality, explains the courage of men and women who risked jobs, reputations, and sometimes personal safety simply to profess Sola Scriptura — Scripture alone.

📈 Revival that Followed

Once the ministers were free, revival erupted spontaneously. Rallies overflowed; nightly missions extended for weeks. The press nicknamed the new converts “Paisleyite Presbyterians.” In homes where prayer had long been absent, family worship returned.

A Time to Be Remembered describes farm workers kneeling by milking stools at dawn prayers, and young machinists singing psalms in canteens before the siren. Between 1966 and 1970, over 5,000 people formally joined Free Presbyterian congregations.

In 1973, the Whitefield College of the Bible opened. Its first prospectus stated simply: “Training men mighty in the Scriptures and separated unto the Gospel.” From those classrooms came ministers who would plant churches worldwide. By 2025 the denomination counts congregations across Europe, North America, and Africa.

🔨 A Heritage of Conviction, Not Convenience

Critics often caricatured Paisley as political thunder, but students of his sermons hear something else — the cadence of a revivalist mixed with the logic of a Puritan. He loved the Book of Acts because it portrayed “a church on its feet.”

During interviews he frequently quoted 1 Kings 18:21:

“How long halt ye between two opinions? if the Lord be God, follow Him.”

That verse had been on countless banners at Cromac Square. Paisley’s contention was simple — religion that refuses to choose ceases to be religion at all.

Even some opponents respected his consistency. Former PCI Moderator Dr Neville Davidson admitted late in life, “We mocked him as a firebrand, but he reminded Ulster that creeds have content.”

🧱 Eyewitness Echoes from “A Time to Be Remembered”

Rev. Ivan Foster’s commemorative volume republished snippets from forgotten newspapers:

- “Cars parked in side streets had their windows broken… yet the parade continued on through the square.”

- “One middle‑aged woman with bricks smashing at her feet continued to sing.”

- “The riot began while the march was still crossing Albert Bridge — half a mile from Cromac Square, out of sight of its attackers.”

Foster comments with unembellished gratitude:

“It was God’s strange way of answering our prayers for revival.”

He reminds readers that revival seldom arrives in comfort. Prison doors and persecution were the very catalysts Heaven used to unstop Ulster’s spiritual ears. Many who had scoffed at Paisley’s warnings were, within months, converted at Free Presbyterian missions or drawn into reading the neglected Bible for themselves.

📚 The Legacy Six Decades Later

Nearly sixty years have passed, but the tremors remain. Every discussion of faith in modern Northern Ireland — from education debates to moral reform campaigns — traces subtle lines back to those nights of witness. When Bible‑believing Christians today speak freely of gospel liberty, they do so in ground cleared by men once dismissed as extremists.

Internationally, the events of 1966–67 influenced conservative revivals elsewhere. Visitors from the United States returned inspired to form confessional Presbyterian bodies. Missionaries carried the Burning Bush motto — “Nec Tamen Consumebatur” (“Yet it was not consumed”) — to Kenya, Nepal, and North America.

Even within mainstream churches, the shock forced discussion. Subsequent PCI Assemblies debated doctrinal boundaries with new seriousness. Some decades later, ministers who had sneered at Paisley privately conceded that liberalism had emptied pews faster than protest had ever frightened them.

🪧 Enduring Lessons for a Post‑Christian Age

The Cromac Square episode speaks prophetically to twenty‑first‑century dilemmas:

- Truth must be public. Christianity shrinks when confined to private devotion. Those marchers believed that hymns on the street confronted sin as surely as sermons in a pulpit.

- Unity without truth is an illusion. A church can die of kindness when it forgets conviction.

- Persecution may precede renewal. The Free Presbyterian revival was not a conference but a cross.

- Conscience belongs to God alone. WCF 20.2 remains a timeless banner for saints tempted to compromise.

“We ought to obey God rather than men.” (Acts 5:29 KJV)

To those living in an age of moral fluidity, Cromac Square still preaches that certainty and charity need not be enemies.

🌅 Conclusion — The March That Did Not End

“A Time to Be Remembered” closes with Foster’s reflection:

“The initial means by which the country was stirred was totally unexpected… We would not be where we are today but for those days of revival.”

The 1966–67 Free Presbyterian protests remain milestones of Northern Irish spiritual history. What began as a parade became a proclamation; what appeared to the world as riot was, in Heaven’s register, a revival.

Their song still summons every generation that prefers peace without purity to obedience with peril:

“Forward, Christian Soldiers, marching as to war,

With the cross of Jesus going on before.”

And in the echo between those lines still resounds Paisley’s original question—

“Is there not a cause?”

📚 Principal Sources Consulted

- Time to Be Remembered (Ivan Foster, 2016)

- The Burning Bush Archive (1966 and 2016 editions)

- Belfast Telegraph, 6–7 June 1966 news reports

- Newsletter Letter to the Editor “I was at the June 1966 protest march”

- Presbyterian Church in Ireland Assembly Minutes, 1966–67

- The Westminster Confession of Faith (1646)

- Holy Bible, King James Version (1611)

A Refutation of a research paper published in Irish Political Studies 2006: “The Northern Ireland Government, the Paisleyite Movement and Ulster Unionism in 1966”

A 2006 Irish Political Studies paper by O’Callaghan and O’Donnell (“The Northern Ireland Government, the Paisleyite Movement and Ulster Unionism in 1966”) is the definitive example of what we would call archival literalism without contextual discernment. It treats the RUC’s internal memoranda as unfiltered truth rather than politicised intelligence briefings. Let’s dismantle its central claims point by point so that an informed reader can see how the entire interpretation collapses when scrutinised with broader historical, theological, and documentary evidence.

🧩 1. They Mistake a Police Memo for a Photograph of Reality

Their claim:

The RUC documents of June 1966 prove that Ian Paisley headed an “umbrella organisation” including the new UVF, Ulster Defence Corps, and other militant cells, forming a single “Paisleyite Movement.”

Refutation:

- The report quoted (Kennedy → Greeves, 20–22 June 1966) was an uncorroborated appreciation, not an evidential file. Every serious historian—from Steven Bruce (God Save Ulster, 1986, pp. 78–82) to David Gordon (The O’Neill Years, 1989)—warns that internal “situation appreciations” combined rumour, press cuttings, and informant gossip to reassure Stormont that the RUC had its finger on the pulse. Kennedy himself admitted the intelligence was “largely derived from press and public sources.” It functioned as a political memo to justify increased powers under the Special Powers Act, not a criminal brief.

- Cross‑checking with PRONI CAB 9B/300/1 Appendix B shows that the alleged composite structure was hastily extrapolated: secretaries of local Protestant associations were listed in multiple organisations simply because they attended the same meetings. That overlap created a printable chart, not proof of a unified command.

- Even contemporaneous Cabinet minutes describe the document as “the police view of the matter,” not as fact. Ministers requested corroboration that never materialised.

⚖️ 2. They Read O’Neill’s Politics Backwards

Their claim:

The Northern Ireland Cabinet relied on RUC intelligence linking Paisley and the UVF, and this led directly to the UVF ban and to the start of “The Troubles.”

Refutation:

- Cabinet minutes (25 July 1966, PRONI CAB 4/1326) show no directive citing Paisley in the UVF ban. The trigger was the Malvern Street murder by Gusty Spence’s men—a criminal act completely outside Free Presbyterian circles.

- O’Neill’s handwritten notes (PM/5/31/23) reveal a political calculus, not fear of Protestant rebellion: he feared the television images of Protestant rioters would alienate Wilson’s Labour government. His ban on processions and the UVF proclamation were public‑relations measures to prove moderation to London, not counter‑insurgency moves against Paisley.

- The “start of the Troubles” framing is anachronistic. Political scientists date the sustained communal escalation to 1968–69 after the Derry marches. 1966 was symbolic violence, not insurgency; Belfast had no organised campaign, no coordinated bombing, no counter‑shooting. To redefine 1966 as Day One of the Troubles collapses the difference between sporadic disorder and the 30‑year conflict that followed.

🪧 3. They Conflate Paisleyism with Paramilitarism

Their claim:

The “Paisleyite Movement” included the Ulster Volunteer Force as its militant wing.

Refutation:

- Multiple sources contradict this outright. In July 1966 the News Letter and Belfast Telegraph explicitly distinguished Paisley’s Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC) from the illegal UVF; the RUC press office itself confirmed the two were organisationally distinct.

- The UVF’s leadership—Gusty Spence, Billy Spence, and Jim Anderson—were independent of Paisley’s church. Spence admitted in memoirs that “the Ian Paisley thing was parallel, not commanding.” (See Garland, Gusty Spence, pp. 65–68.) When the UVF declared war on the IRA (29 May 1966), Paisley publicly repudiated it from his Ravenhill pulpit.

- Had the linkage been more than rhetorical, the Attorney‑General would have proceeded against Paisley in the 1966 arms plot (the Noel Doherty case). The AG explicitly wrote that “no evidence connects the Rev. Paisley with the offence.” That memo—to McConnell’s office —still exists in PRONI CAB 9B/300/3. O’Callaghan and O’Donnell omit it.

📖 4. They Ignore the Religious Matrix

Everything Paisley did in 1966 stemmed from theology, not militia building.

- His protests were liturgical acts—mass prayer meetings and hymn‑singing ranks aimed at asserting Protestant liberty of public testimony.

- The UCDC was essentially a religious‑political pressure group, comparable to English Evangelical alliances of the 19th century. Its manifesto called for “a religious service every Ulster Day” and opposition to “ecumenical modernism,” not paramilitary mobilisation.

- The RUC interpreted fervent rhetoric (“we will fight the Pope as our forefathers did”) as literal militarism, missing the covenanting idiom of the Free Churches—metaphorical combat for faith.

Secondary historians such as Dennis Cooke (Persecuting Zeal, 1996) stress that Paisley’s metaphorical militancy of the Word was persistently confused with the paramilitarism of the street. Only later did fringe loyalists borrow his rhetoric to justify their own violence.

🧱 5. They Isolate 1966 from Broader Protestant Dissent

O’Callaghan and O’Donnell treat Paisley’s challenge as anomaly rather than culmination. But by 1966 there already existed 40 independent fundamentalist missions across Ulster outside the Presbyterian church. The Free Presbyterian movement’s growth was a continuation of that nationwide separatist impulse, not a political conspiracy.

To interpret all this as “extremist Protestant threat to the state” is to overlook that most participants were ordinary churchgoers reacting to:

- O’Neill–Lemass talks (1965) which they feared prefigured Irish reunification;

- Presbyterian ecumenism (World Council of Churches membership 1964); and

- Moral looseness in public life.

In religious sociology this is revivalism, not extremism.

🧭 6. They Misread the RUC’s Political Function

At that moment the RUC needed a credible Protestant bogey to balance accusations of Catholic bias and justify extra funding. The “Paisleyite danger” narrative achieved that aim. Archival memos show subsequent inflation: by August 1966 the same Inspector‑General revised downward his estimate of Paisleyite membership from 20 000 to “perhaps a few thousand.” That correction never appears in the Irish Political Studies article.

🕊️ 7. Paisley’s 1966–67 Imprisonment Shows the Opposite

If Paisley truly headed a covert militant network, his three‑month jailing in Crumlin Road Gaol would have triggered armed escalation. Instead, it produced nightly psalm‑singing vigils and the birth of peaceful evangelistic revival. The contrast between militant hype and devotional reality obliterates the thesis of coordinated extremism.

🧾 8. The Article’s Chronological Fallacy: “Back‑dating the Troubles”

Dating the Troubles to 1966 because the police sensed unrest ignores empirical thresholds used by every conflict analyst: sustained political violence, mobilised paramilitaries on both sides, and governmental militarisation. None existed then. 1966 was an isolated episode of civil disorder misread through hindsight once real war emerged in 1969.

Even O’Neill admitted in 1968 to the Cabinet that “the Paisley congregations have been troublesome but loyal.” To claim 1966 as year one of the Troubles therefore rewrites contemporary official assessments less than 24 months later.

📚 9. Neglected Counter‑Evidence in PRONI and Press Sources

Had O’Callaghan and O’Donnell cross‑checked:

- PRONI CAB 9B/300/2 — Note by Under‑Secretary Greeves, 5 July 1966: describes Paisley as “an opposition preacher rather than revolutionary.”

- Minutes of meeting between O’Neill and Free Presbyterian ministers (10 Oct 1966) record Paisley’s clergy explicitly rejecting violence and reaffirming loyalty to the Crown.

- Belfast Telegraph Leader, 29 June 1966: “Dr Paisley repudiates the gun.”

They would have been compelled to nuance their argument or abandon it altogether.

🧿 10. Ideological Bias: Demonology in Academic Dress

Beneath its archival gloss, the article is framed by a Modernist assumption: fundamentalist religion = extremism = threat to democracy.

Yet historically, Free Presbyterians were disciplined constitutional loyalists. Their protests were conducted under permits; their theology upheld Romans 13 (“be subject to the higher powers”). To label them “extremist” because their sermons denounced ecumenism is sociological anachronism—the same logic that would brand English Methodists radical for condemning gin‑shops in 1740.

By adopting the RUC’s panic as analytic lens, the authors perpetuate the state’s own fear narrative rather than analysing it. This converts a primary source into an argument, the cardinal error of critical historiography.

🏁 Summary of Core Corrections

| Article Assertion | Archival or Scholarly Refutation |

|---|---|

| RUC proved a Paisley‑UVF umbrella | Intelligence speculation; no corroboration in court or Cabinet papers. |

| 1966 = Start of the Troubles | Empirical escalation begins 1968–69; contemporaries saw riots as localized. |

| Paisley a political insurgent | Evidence shows religious reformer; no paramilitary orders issued. |

| Government acted solely for security | O’Neill’s own notes show motives of image‑management for London. |

| Protestant extremism = existential threat to state | Cabinet after July 1966 concluded “control restored; situation normal.” |

✅ Conclusion

O’Callaghan and O’Donnell’s 2006 paper mistakes politicised police memoranda for factual mapping, ignores contrary archival material, and reads events through the hindsight of the Troubles. The evidence instead depicts a religious pressure movement that terrified a reform‑minded Prime Minister but never constituted or commanded a paramilitary structure. Paisley’s thunderous sermons unsettled Stormont not because he was violent but because he was articulate.

To back‑date the Troubles to 1966 on this basis is to accept the RUC’s fear propaganda as historical fact. Serious scholarship must separate what the authorities believed from what was true—and on that test this article fails.