Table of Contents

The spiritual landscape of Carryduff, a quaint village in County Down, Northern Ireland, is richly layered with stories of God’s sovereign interventions across generations. From the profound outpouring of the Holy Spirit during the 1859 Ulster Revival to the humble, prayer-filled origins of Carryduff Free Presbyterian Church in the 1960s and 1970s, the area has been marked by fervent faith, deep conviction, and transformative gospel work. These epochs, separated by over a century, reflect a continuum of evangelical zeal in Ulster—rooted in prayer, biblical fidelity, and a burden for souls. Drawing from historical records, newspaper accounts, revival chronicles, and denominational testimonies, this article explores the 1859 Revival’s sweeping impact, with a focused lens on Carryduff, before tracing the modern establishment of Carryduff Free Presbyterian Church. Together, they illustrate how God’s grace has sustained a witness in this corner of Ulster, inspiring calls for fresh revivals in our day.

The 1859 Ulster Revival: A Divine Awakening and Its Enduring Echoes in Carryduff

The mid-19th century was a time of profound spiritual stirring across the British Isles, but nowhere was this more dramatically evident than in Ulster, Northern Ireland. The 1859 Ulster Revival, often hailed as the “Year of Grace,” swept through the province like a mighty wind, igniting prayer meetings, convicting sinners, and leading to an estimated 100,000 conversions in a single year. This extraordinary outpouring of the Holy Spirit not only transformed individuals and communities but also left an indelible mark on Ulster’s religious landscape, fostering a conservatism that persists to this day. While the revival’s epicentre was in County Antrim, its flames spread southward to County Down, touching villages like Carryduff with deep conviction and renewal.

Origins: From Humble Prayer to Holy Fire

It began in the spring of 1856, when Mrs Colville, an English lady from Gateshead, arrived in Ballymena with time and money to devote to God’s work. She conducted house-to-house visitation to win souls for Christ. In November 1856, she visited Miss Brown in Mill Street, Ballymena, where a discussion on predestination and freewill was underway among Miss Brown, two other ladies, and a young man named James McQuilkin, a linen warehouse worker from the parish of Connor, five miles away. Mrs Colville emphasised seeking a personal interest in the Saviour and the need for the new birth, profoundly impacting McQuilkin spiritually. Shortly after, he experienced a saving knowledge of Christ and became a key figure in the subsequent revival.

McQuilkin, who had previously reared fighting cocks but now had a changed outlook, returned weekly to Kells from his work in Ballymena. Influenced by Rev John Moore, minister of Connor Presbyterian Church, he gathered converted friends—Jeremiah McNeilly, John Wallace, and Robert Carlisle—and started a Sabbath School at Tanneybrake near Connor. Feeling inadequate, in autumn 1857 they repurposed an old schoolhouse near Kells for prayer meetings to seek God’s blessing on the Sabbath School.

By December 1857, the group saw the conversion of a young man they had prayed for, followed by weekly conversions in the district. At the spring 1858 communion in Connor Church, a special sense of God’s presence led to ongoing conversions throughout the parish. By year’s end, about fifty men met regularly for prayer at the Old Schoolhouse (women held separate meetings).

On 9 December 1858, Samuel Campbell from Ahoghill, working in Kells, came to Christ through the Connor prayer meeting’s influence and prayers. He witnessed to his family, leading his brother and sister to seek the Saviour, though his brother John initially resisted. Campbell persisted, confronting John during a shooting match in the fields with a message from the Lord Jesus, causing John to tremble under conviction of sin. John endured weeks of soul agony at home before assurance of forgiveness. Rev Frederick Buick of Trinity Church, Ahoghill, encouraged by the Campbells’ conversions, arranged a meeting on 22 February 1859 in Ballymontena Schoolhouse where Connor converts would share their experiences. Overcrowding prompted relocation to Trinity Church, profoundly impacting Ahoghill and spurring prayers for revival.

On 14 March 1859, at the thanksgiving service closing the spring communion in First Presbyterian Church, Ahoghill—pastored by Rev David Adams, who had prayed for revival since 1841 in a new 1200-seat building—about 3,000 people gathered, conducted by Adams. Connor convert James Bankhead prayed and attempted to speak with claimed superior authority, alarming Adams amid crowding risks. Adams cleared the building; outside in the muddy village square during rain, Bankhead and others addressed the crowd from house steps for hours, with many falling in distress and crying for mercy.

This revival, originating in Connor in 1858 and spreading to Ahoghill in 1859, began as prayer meetings and progressed to public outbreaks, initially unknown in nearby Ballymena but soon to expand. Historian J. Edwin Orr described it as “the first outbreak of mass conviction of sin to occur anywhere in the British Isles during the mid-19th century,” noting its profound impact on Ireland, rivalling the days of St. Patrick. Unlike scripted evangelistic campaigns, this was a sovereign work of God, sparked by laypeople rather than clergy, and fuelled by grassroots prayer.

The socio-economic context played a role: Ulster in the 1850s was recovering from the Great Famine (1845-1852), which had decimated Ireland’s population through starvation and emigration. Amid lingering hardship, political tensions, and a nominal Christianity in many churches, the revival offered hope and moral renewal. It drew from earlier evangelical influences, such as the Methodist revivals of the 18th century and the 1820s-1830s stirrings in Ulster, but distinguished itself by its scale and spontaneity.

The Spread: From Antrim to the Ends of Ulster

From its Antrim origins, the revival radiated outward, engulfing towns like Coleraine, Belfast, and Londonderry in the north, before sweeping into Counties Down, Tyrone, and beyond. By summer 1859, it had crossed into Scotland, Wales, and England, influencing figures like Charles Spurgeon and inspiring global missions. In Coleraine, for instance, an evangelist preached at the fairgrounds until dusk, then moved to the newly built Town Hall, where thousands gathered—leading to such conviction that the planned inaugural dance was cancelled. Open-air meetings of 25,000 were common, with reports of entire villages transformed.

The revival transcended denominational lines, affecting Presbyterians, Methodists, Anglicans, and even some Roman Catholics. Ministers like Rev. William Gibson (author of The Year of Grace) documented the events, emphasising that “God worked!” without human orchestration. It spread through word-of-mouth, newspapers like The Banner of Ulster, and travelling testimonies, reaching as far as Londonderry and Armagh by autumn.

Characteristics: Conviction, Prostrations, and Societal Transformation

The 1859 Revival was marked by intense spiritual phenomena that set it apart from typical religious meetings. Central to it were prayer meetings, which overflowed churches and spilled into streets, barns, and fields. Participants experienced deep conviction of sin, often manifesting physically: people would cry out, fall prostrate (known as “stricken” or “slain in the Spirit”), tremble, or weep uncontrollably as they confronted their need for salvation. These were not induced by hype but by the Holy Spirit’s sovereign power, leading to genuine repentance and faith in Christ.

Revival chronicler Henry Grattan Guinness noted that it brought “spiritual fervour and societal transformation,” with public houses closing, crime rates plummeting, and family worship reviving. All walks of life were touched: farmers, factory workers, the elderly, and youth. In one account, a preacher in Coleraine yelled Scriptures while the crowd prayed, resulting in mass conversions. Controversies arose—critics accused it of hysteria or emotionalism—but defenders like John Weir, in his 1860 book The Ulster Awakening, provided eyewitness testimonies to affirm its authenticity.

The revival’s fruits were tangible: churches grew exponentially, with some reporting membership doublings. It fostered moral reforms, reduced drunkenness, and boosted missionary zeal, influencing global evangelism for decades.

Impact in County Down: A Focus on Carryduff

While Antrim was the revival’s cradle, County Down felt its full force by late spring 1859, with hotspots in Comber, Saintfield, and Killinchy. Carryduff, a rural village southeast of Belfast, was drawn into this divine tide, experiencing a localised but profound awakening that mirrored the province-wide movement.

According to a July 2, 1859, report in The Banner of Ulster, the revival reached Carryduff about a month prior, igniting congregational prayer meetings at Carryduff Presbyterian Church (located on Church Road, the historic congregation still active today). These gatherings quickly outgrew the church building, drawing crowds so large that meetings spilled outdoors. The report highlights: “Every day and night since that time, many have been stricken by the Spirit with deep conviction, and have found pardon and peace in the Saviour.” A unique aspect in Carryduff was the revival’s impact on older generations: “Nearly all who have been brought under His extraordinary influence are persons advanced in age—some very old—while few young people have yet been struck down.” This contrasted with youth-focused outbreaks elsewhere, suggesting a targeted work among the community’s elders, perhaps addressing long-held nominal faith or unrepented sins.

Carryduff’s proximity to Comber—where the revival erupted dramatically in late May, with hundreds converted and prostrations in the streets—amplified its effects. Rev. J.M. Killen of Comber documented similar scenes: factories halted as workers fell under conviction, and prayer meetings ran continuously. In Carryduff, the revival fostered unity, with Presbyterians leading the charge but likely drawing from surrounding Methodist and Anglican influences. Societal changes followed: reduced vice, strengthened families, and a renewed emphasis on Scripture.

Though specific numbers for Carryduff are scarce (unlike Coleraine’s thousands), the revival’s ripple effects are evident in the area’s enduring evangelical heritage. The UK Wells Revival database lists Carryduff Presbyterian Church as a key site, noting prayer meetings as the catalyst. This aligns with broader County Down reports, where the revival led to church expansions and missionary societies.

Legacy: Enduring Fruits and Modern Resonance

The 1859 Revival’s impact was staggering: an estimated 100,000 converts in Ulster alone, with societal reforms that curbed alcoholism, crime, and immorality. It bolstered Protestantism in Northern Ireland, contributing to its religious conservatism, as noted by figures like Ian Paisley. Globally, it inspired revivals in Britain and beyond, influencing the Holiness Movement and modern Pentecostalism.

In Carryduff, the legacy lives on through strengthened church life and a spiritual lineage that echoes in congregations like Carryduff Free Presbyterian Church. Founded much later amid 20th-century separatist movements, it draws from the revival’s emphasis on prayer, conviction, and biblical fidelity—evident in its celebration of Ulster’s evangelical history. As one modern reflection puts it, the revival reminds us that “God came down” in barns and schoolhouses, transforming ordinary places into altars of grace. As historian Edwin Orr observed, it was a work that “made a greater impact spiritually on Ireland than anything since St. Patrick.” May its story stir hearts anew for fresh visitations of the Holy Spirit.

The Beginnings of Carryduff Free Presbyterian Church: From Murphy’s Loft to a Faithful Witness

Building upon the evangelical foundations laid during the 1859 Revival, the story of Carryduff Free Presbyterian Church represents a modern chapter in the village’s spiritual narrative—a testament to God’s providential guidance, fervent prayer, and the pioneering spirit of faithful believers in Ulster’s evangelical tradition. Rooted in the separatist ethos of the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster (FPCU), founded by Rev. Ian Paisley in 1951, the Carryduff congregation emerged from modest, makeshift beginnings in the 1950s and 1960s, with the witness taking shape through youth fellowships and early evangelistic efforts.

The Early Witness: From Youth Fellowship to Murphy’s Loft

The origins of the Free Presbyterian witness in Carryduff trace back to the formation of a young people’s fellowship following the June 1955 Jack Schuler crusade at Belfast’s Kings Hall. This fellowship provided a vital space for young believers to learn to pray publicly, share the Gospel, and grow in faith. Initially connected to Carryduff Presbyterian Church, the group encountered challenges that led to its relocation to Murphy’s Loft in Carryduff, near Belfast—a simple, informal venue that became the hub for continued Gospel outreach.

Murphy’s Loft served as the setting for grassroots gatherings in the late 1950s and early 1960s, fostering a sense of community and spiritual hunger among young people disillusioned with perceived compromises in mainstream Presbyterianism.

Among those involved in the Carryduff fellowship at Murphy’s Loft was Dr. Frank McClelland, who later reflected on these formative years in a testimony given at Carryduff Free Presbyterian Church. Dr. McClelland described how he initially made a false profession under pressure in an inquiry room, only to live with years of inner conviction until a genuine conversion during the 1955 Jack Schuler mission at the King’s Hall brought true peace and assurance. He recalled the early youth fellowship gatherings at Murphy’s Loft, the hearty singing, and the powerful preaching of Rev. Ian Paisley, whose ministry profoundly influenced him. His connection to Carryduff continued through these early days, and he went on to serve faithfully in ministry, eventually spending nearly 50 years in North America while always regarding Carryduff as home.

In May 1959, a visiting preacher to the loft, Burt Wheeler, led to the conversion of Mr. Wilfred Crawford, a founding member of the Free Presbyterian witness. On 4 May 1960, a pivotal Gospel mission led by Rev. Ian Paisley took place, during which, the late Rev. James McClelland—then just 18 years old—found faith in Christ. Alongside his friend Harry Agnew, he prayed a sinner’s prayer, drawing on the promises of 1 John 1:7 (“the blood of Jesus Christ his Son cleanseth us from all sin”) and 1 John 1:9. This conversion experience ignited a lifelong passion for evangelism and marked a key moment in the emerging witness.

From 1960 to 1964, Robert Lowe, Wilfie Crawford, and the McClelland brothers immersed themselves in the Carryduff fellowship at Murphy’s Loft, learning to share testimonies and evangelise. Influential speakers, such as Pastor Fenton and Mrs. Seth Sykes (whose singing at the organ deeply moved them), shaped their approach to ministry. These gatherings at Murphy’s Loft embodied the FPCU’s principle of “starting small but standing firm,” mirroring Paisley’s own beginnings in modest venues, and laid essential groundwork for future development.

The Derelict Killynure National Schoolhouse: A Symbol of Revival from Ruins

As the witness developed, attention turned to a more permanent base. The physical foundation of Carryduff Free Presbyterian Church lies in the historic Killynure National Schoolhouse, which was located at 87 Killynure Road, Carryduff, Belfast, BT8 8EB.

Built in 1817 through public subscriptions, and adopted into the National Schoolhouse register after the Stanley Letter (1831), this modest structure served as a local school for nearly two centuries, undergoing refurbishment in 1871 to accommodate growing needs. It educated generations of children until 1968, when a new primary school opened in Carryduff, rendering the old building obsolete. For several years afterward, the schoolhouse fell into disrepair—derelict, vandalised, and abandoned, its windows smashed and interiors stripped by neglect and mischief.

It was in this unlikely setting that the next phase unfolded. In 1976, the late Mr. Robert Lowe, a local resident of Killynure deeply concerned about the spiritual vacuum in his neighbourhood, saw potential in the forsaken building. Motivated by a burden for souls and aligned with the FPCU’s emphasis on gospel outreach, Lowe approached the fellow trustees of the property. With their approval, he spearheaded efforts to repurpose the space for Christian ministry, specifically to establish a Free Presbyterian Sabbath School aimed at teaching the truths of the Gospel to local children.

A Dramatic Act of Faith: Crawling Through the Window and Praying on the Floor

The origins of this endeavour are steeped in a remarkable story of determination and divine calling, often recounted in Free Presbyterian circles as an emblem of Paisley’s bold evangelism. Before formal renovations began, the building was locked and inaccessible, its doors barred due to years of disuse. Undeterred, the late Mr. Robert Lowe and Rev. Ian Paisley—then the dynamic founder and moderator of the FPCU—took extraordinary measures to claim the space for God’s work. According to cherished oral histories and denominational testimonies, the two men crawled through a side window of the vandalised schoolhouse, entering the dusty, debris-strewn hall. Once inside, they knelt (or even prostrated themselves) on the bare floor, pouring out their hearts in prayer. Their supplication was specific and fervent: that God would sovereignly open a Free Presbyterian witness in Carryduff, a place where biblical separation, sound doctrine, and soul-winning evangelism could flourish amid the spiritual and political turbulence of 1970s Northern Ireland.

This act of faith echoed the FPCU’s founding principles—Paisley’s own journey from a small gospel hall in Crossgar to a denomination emphasising protest against ecumenism and modernism. The prayer in the schoolhouse hall was not mere symbolism; it marked a spiritual consecration, invoking God’s blessing on what would become a beacon of light in County Down. As Paisley later reflected in various sermons, such humble beginnings reminded believers of biblical precedents, like Nehemiah rebuilding Jerusalem’s walls amid opposition, or the early church meeting in homes and upper rooms.

The Foundational Gospel Mission: Led by Rev. Ian Paisley

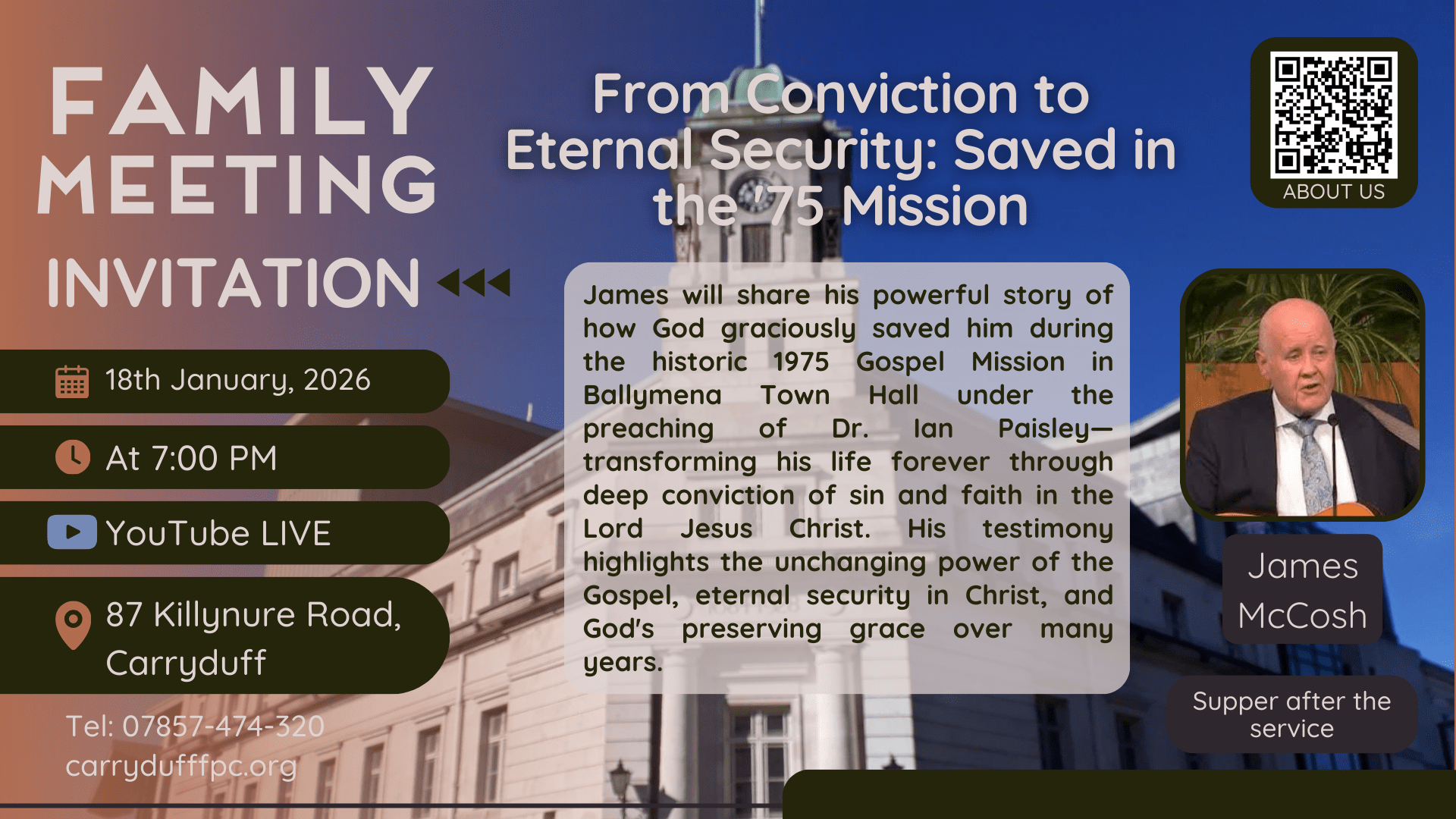

The renovated schoolhouse’s inaugural event was a pivotal two-week Gospel Mission in 1976, led by Rev. Ian Paisley himself. This campaign was a direct outgrowth of the earlier prayers and gatherings, designed to evangelise the Carryduff area and establish a firm Free Presbyterian presence. Paisley, known for his thunderous preaching and unyielding defence of Protestant truth, drew crowds with messages centred on sin, repentance, and salvation through Christ alone. His sermons, often drawing from texts like Malachi 3:10 or Acts 3:19, emphasised God’s ability to “open the windows of heaven” and bring “times of refreshing.”

The mission was marked by deep conviction and spiritual breakthroughs. Several souls were converted during the meetings, experiencing the Holy Spirit’s power in ways reminiscent of Ulster’s historic revivals, such as the 1859 Awakening or the 1975 Ballymena Mission (also led by Paisley). Attendees recall an atmosphere of solemnity, with prayers echoing through the newly restored hall and testimonies of changed lives emerging. This event not only launched the Sabbath School but also solidified the work as an outreach arm of Martyrs Memorial Free Presbyterian Church in Belfast, under Paisley’s oversight.

For the next two decades, the Killynure site operated as a non-constituted mission station, hosting weekly Sabbath Schools in the afternoons and evening services at 8:30 pm. Services were led by visiting FPCU ministers and lay preachers, supervised by Rev. David McIlveen of Sandown Road FPC and the Martyrs Memorial Kirk Session. With help from local contractor Mr. Wilfred Crawford, the trustees renovated the interior and exterior, including building a new pulpit for gospel proclamation—transforming the vandalised relic into a house of worship.

As families grew in conviction and numbers, the group petitioned for full congregation status, which was granted on February 18, 1996. Three years later, on March 31, 1999, Rev. David McLaughlin was ordained and installed as minister, ushering in an era of growth with new conversions and community engagement.

Legacy and Ongoing Witness: Bridging Past and Present

From the fervent prayer meetings of 1859 to the early fellowship in Murphy’s Loft and the prayerful consecration of the Killynure Schoolhouse in 1976, Carryduff’s spiritual heritage reflects God’s faithfulness across eras. The 1859 Revival’s emphasis on conviction and renewal finds echoes in the FPCU’s commitment to separation and evangelism, reminding us that true awakening begins in humble places—whether a schoolhouse in Antrim or a loft in Carryduff. Today, Carryduff Free Presbyterian Church continues to proclaim Christ, hosting services, family nights, and outreach events. As the congregation looks back, it echoes Paisley’s vision: a witness that started in ruins but stands as a “mighty oak” for God’s glory.

For more on the church’s journey, visit carrydufffpc.org or follow @CarryduffFPC on YouTube, Facebook, or X. May these stories inspire renewed prayer for God’s work in our generation!