Table of Contents

How do we recognise a vocation when we see it? A nurse, a police officer, a judge — each uniform tells the public, this person serves in a particular way. Clothing, after all, is never neutral; it declares allegiance, purpose, and identity. Yet when the person clothed is a minister of the Gospel, the question deepens: should a servant of Christ be visibly distinguished, or should humility hide all outward marks of office?

The clerical collar stands at the centre of that tension — to some, it is a visible reminder of spiritual vocation and social duty; to others, an outdated symbol of institutionalism, the kind of “priestly uniform” the Reformers fought to overthrow.

Today, most people associate the white collar with Anglican or Catholic clergy. Yet, paradoxically, the collar, as we recognise it, was formalised not in Rome, but in nineteenth-century Presbyterian Scotland — a Reformed innovation that eventually spread to nearly every denomination.

Its story is not merely about fashion or function, but about how the Church has wrestled for centuries with the meaning of visibility in vocation.

To understand how this emblem of clerical life emerged, we must return to the earliest days of the Reformation — to Luther and Calvin — when the visible marks of “the clergy” were being passionately debated, dismantled, and redefined.

From Cassock to Collar: The Pre-Reformation Background

Before the sixteenth century, Western clergy were marked off by their vestis talaris — the long, black cassock, derived from Roman civil dress. The collar itself did not yet exist; priests often donned albs or amices under the cassock, garments that framed the neck or shoulders but bore no distinct band of white.

For centuries, clothing had functioned as both spiritual and social boundary. A priest’s dress was meant to differentiate him from the layman. But by the eve of the Reformation, such distinctions had become a magnet for criticism. Extravagant vestments, gold-threaded robes, and embroidered mitres came to symbolise a clerical elite more concerned with pomp than piety.

Luther and the “Priesthood of All Believers”

Martin Luther’s revolt in 1517 struck at the very root of this hierarchy. His doctrine of the universal priesthood made obsolete the idea that a particular class of men had mediating power between God and man. In his 1520 tract To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, he thundered:

“It is pure invention that pope, bishops, priests, and monks are called the spiritual estate; while princes, lords, artisans, and farmers are called the temporal estate. That is indeed a fine bit of lying and hypocrisy.”

He continued, with characteristic plainness:

“All Christians are truly of the spiritual estate, and there is among them no difference at all but that of office.”

It followed naturally that Luther and his followers viewed clerical garb with suspicion. While he did not immediately abolish distinctive clothing, he urged moderation and simplicity, warning against outward show, insisting that “these things make neither priest nor layman, Christian nor unbeliever,” and that “all be done soberly and without offence.” (compare 1 Timothy 2:9).

(cf. 1 Timothy 2:9) — “In like manner also, that women adorn themselves in modest apparel, with shamefacedness and sobriety…”

Luther’s message was transparent: purity of conscience was worth infinitely more than ornamental holiness. Garments did not sanctify the man; only faith could.

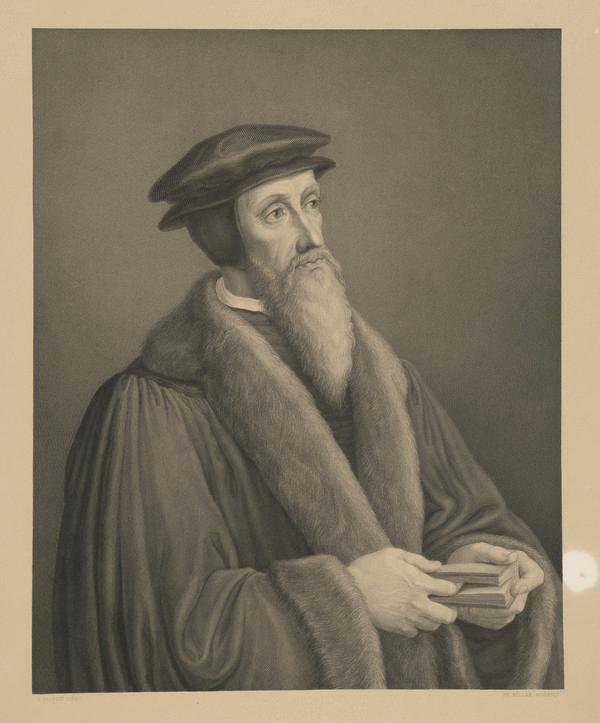

Calvin: Order, Simplicity, and Symbolism

John Calvin, ever more systematic, continued Luther’s balancing act between visible order and spiritual humility. While he rejected both ornamentation and sacramental vesture, he did not advocate total uniformity. In The Institutes of the Christian Religion (Book IV, Ch. 10), he wrote:

“In those external matters which are not necessary to salvation, the Church may freely use her liberty; provided they be done decently and in order, according to the apostle’s word.”

(cf. 1 Corinthians 14:40) — “Let all things be done decently and in order.”

National Galleries of Scotland

Calvin himself wore the black scholar’s robe common among Geneva’s ministers — a practical garment, devoid of sacerdotal meaning. His followers, especially in the Huguenot and Puritan traditions, adopted similar attire: typically black gowns, tabbed necks, and later, the Genevan bands — those two small white strips descending from the collar.It was those bands, not collars, that dominated Protestant clerical fashion from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. They were the visible mark of Reformed ministry: not a priestly symbol, but one of learning and proclamation, aligning ministers more with professors and magistrates than with a mediating priesthood.

Puritans and Presbyterians: The Ascetic Aesthetic

In England and Scotland, the story takes a particularly vivid turn.

The Puritans, with their austere sensibility, faced bitter controversy over vestments. The Vestiarian Controversy of the 1560s pitted reform-minded clergy against bishops defending traditional Anglican robes. The Puritan side cited Scripture directly:

“Whose adorning let it not be that outward adorning of plaiting the hair, and of wearing of gold, or of putting on of apparel.”

(1 Peter 3:3, KJV)

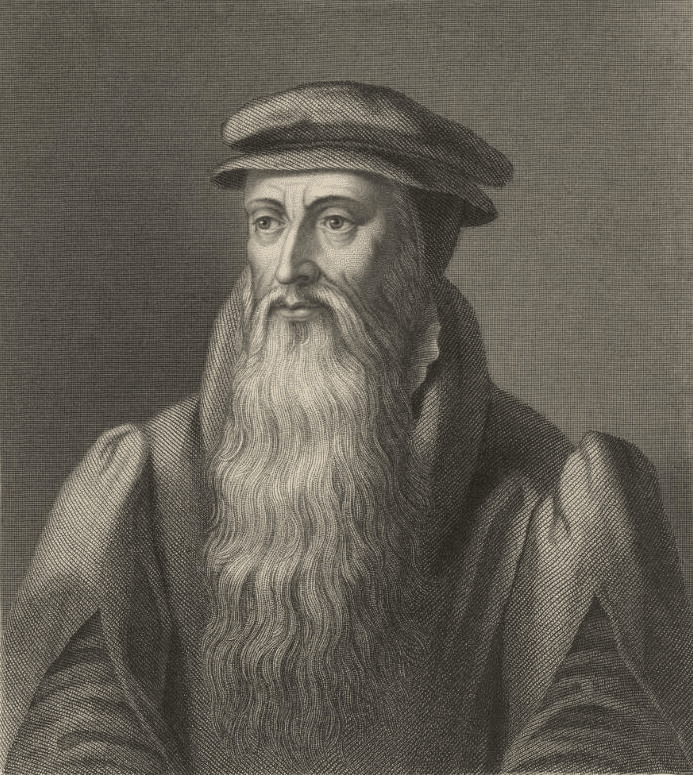

Simplicity was thus elevated almost to the level of a moral principle. The black gown became the symbol of Presbyterian and Puritan preaching — dignified yet unsacramental. In portraits of John Knox, one sees the square cap, the gown, and the long beard, but no collar in the modern sense.

When the Church of Scotland was formally established along Presbyterian lines in 1560, it demanded plainness of apparel among ministers. But by the nineteenth century, something curious began to happen: the Reformed clergy, once iconoclasts of adornment, began to craft a new, modest uniform of their own.

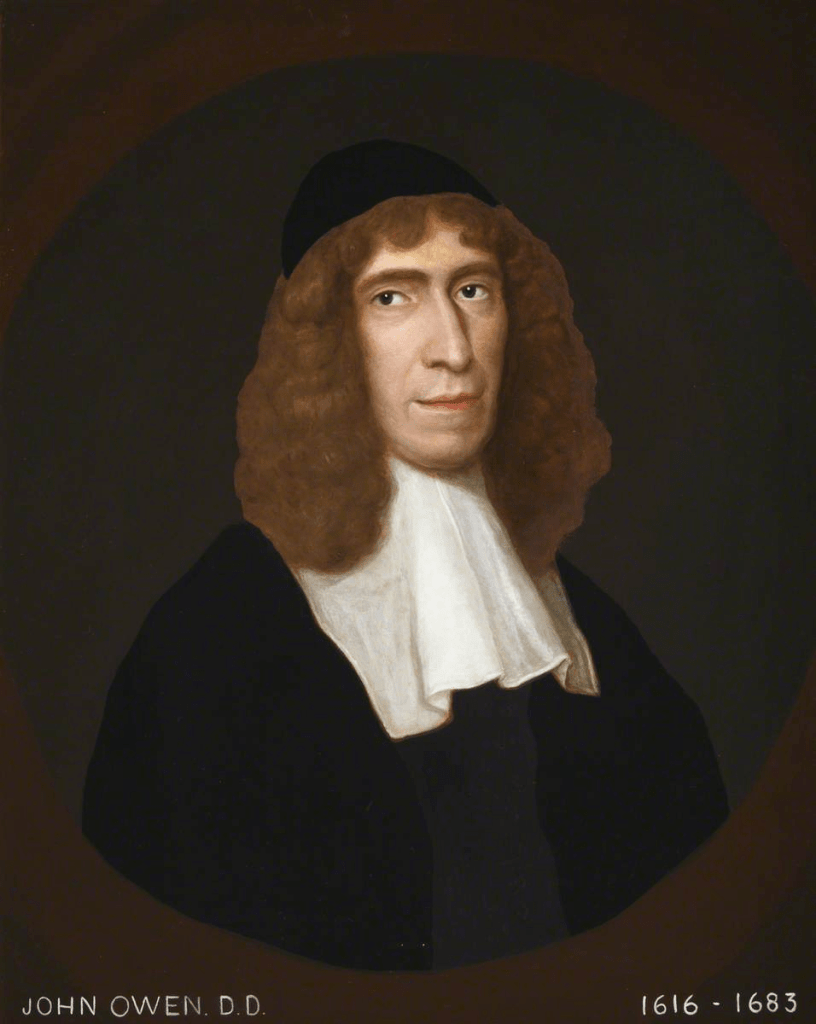

John Owen — The Scholar of Black Cloth and White Bands

Few embodied Calvin’s heritage more profoundly than John Owen (1616–1683), chaplain to Oliver Cromwell and arguably the greatest theologian of English Puritanism. Owen maintained the visual legacy of Geneva: the scholarly gown and white preaching bands.

In his Sermons and Discourses, Owen frequently warned ministers against external religion:

“Men look upon the outside of things; but God seeth the heart.”

Yet he upheld public order and dignity, believing external discipline nurtured inner gravity. His dress symbolised that conviction — black and white; intellect and humility. No priestly vestments, but a learned man’s uniform, pointing to Word and reason as vehicles of grace.

(cf. 1 Samuel 16:7 — “Man looketh on the outward appearance, but the LORD looketh on the heart.”)

The Puritan gown thus evolved into an emblem not of ecclesiastical rank but of theological seriousness. Owen’s Geneva bands were not decoration — they were punctuation marks upon the preacher’s mouth.

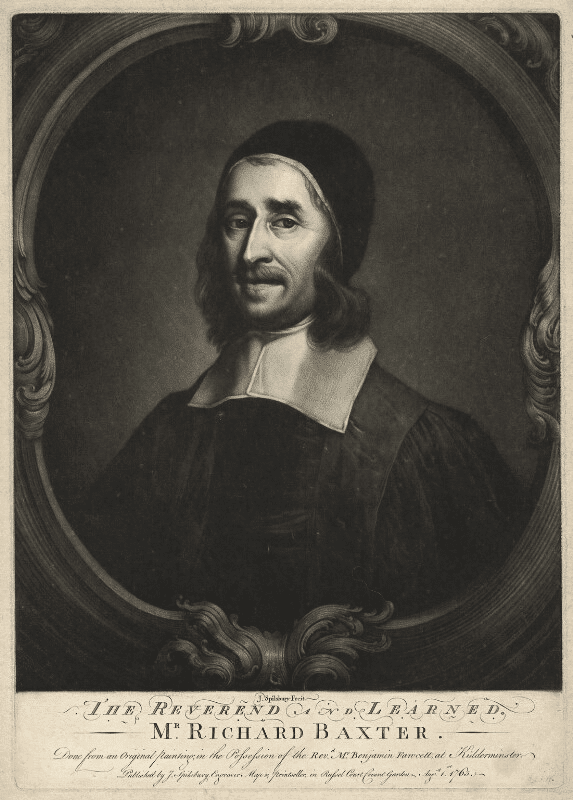

Richard Baxter — The Minister as Moral Physician

Richard Baxter (1615–1691), author of The Reformed Pastor and perhaps the archetype of Puritan conscientiousness, balanced theology with relentless practicality. His black gown and broad Geneva bands were uniform not of pomp but of penitence. In The Reformed Pastor (1656) he admonished ministers:

“Take heed to yourselves, lest your example contradict your doctrine.”

Baxter treated the clerical habit as a tool for discipline — a visible reminder of the gravity of office. He cautioned against vanity yet insisted upon order: neatness that honoured the message without drawing eyes to the man. His attire resembled his prose — plain, sober, durable, crafted for the long labour of pastoral care. For Baxter, the preacher was a kind of moral physician, and his clothing a physician’s uniform — dark, functional, clean — suited to the healing of souls rather than the display of rank.

(cf. Titus 2:7 — “In all things shewing thyself a pattern of good works: in doctrine shewing uncorruptness, gravity, sincerity.”)

Richard Baxter, in The Reformed Pastor (1656) p.206, defended distinctive dress so long as it was not “popish”:

One of our most heinous and palpable sins is Pride... It fills some men’s minds with aspiring desires and designs…

He advocated for a plain and humble clerical dress that would distinguish ministers from the “common sort” of people but without any vanity or excess. He believed that pride was a sin that could manifest even in outward appearance and condemned ministers for dressing in the current fashions, specifically mentioning extravagant “hair and habit”.

Even the Puritans, often caricatured as plain-dress radicals, were split over ministers wearing the black gown and bands in the pulpit, seeing it as one of conscience. The Westminster Directory (1645) abolished “popish” vestments but explicitly retained “a comely and decent habit” for ministers.

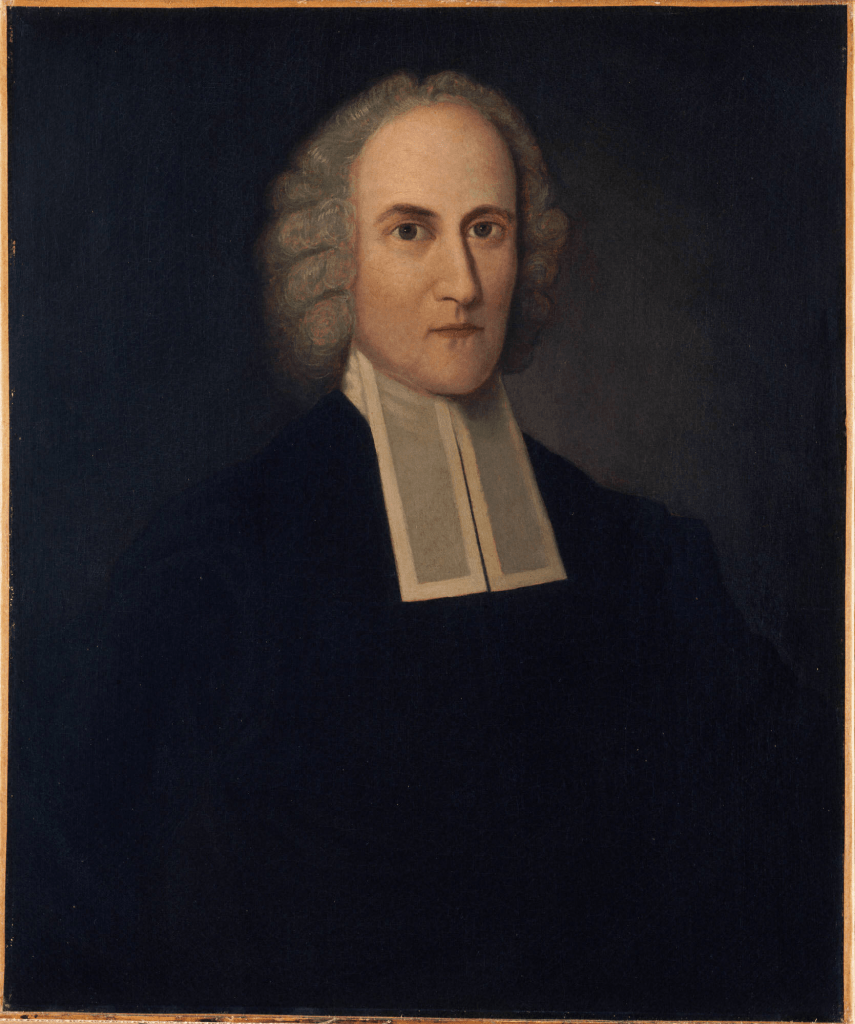

Jonathan Edwards — Piety in Order and Fire

Moving across the Atlantic, Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) carried Puritan manner and matter into American soil. In portraits, he wears the black robe and broad white bands identical to Owen’s. Yet behind that calm attire was a blazing heart.

His sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God (1741) delivered spiritual fire from a visually subdued pulpit. Edwards’s restraint of dress magnified the terror of his words; it was theological theatre through negation.

“There is nothing that keeps wicked men at any one moment out of hell, but the mere pleasure of God.”

His uniform proclaimed intellect and discipline, the antithesis of revivalist spectacle. The later collar would echo that tension — outward simplicity, inward intensity.

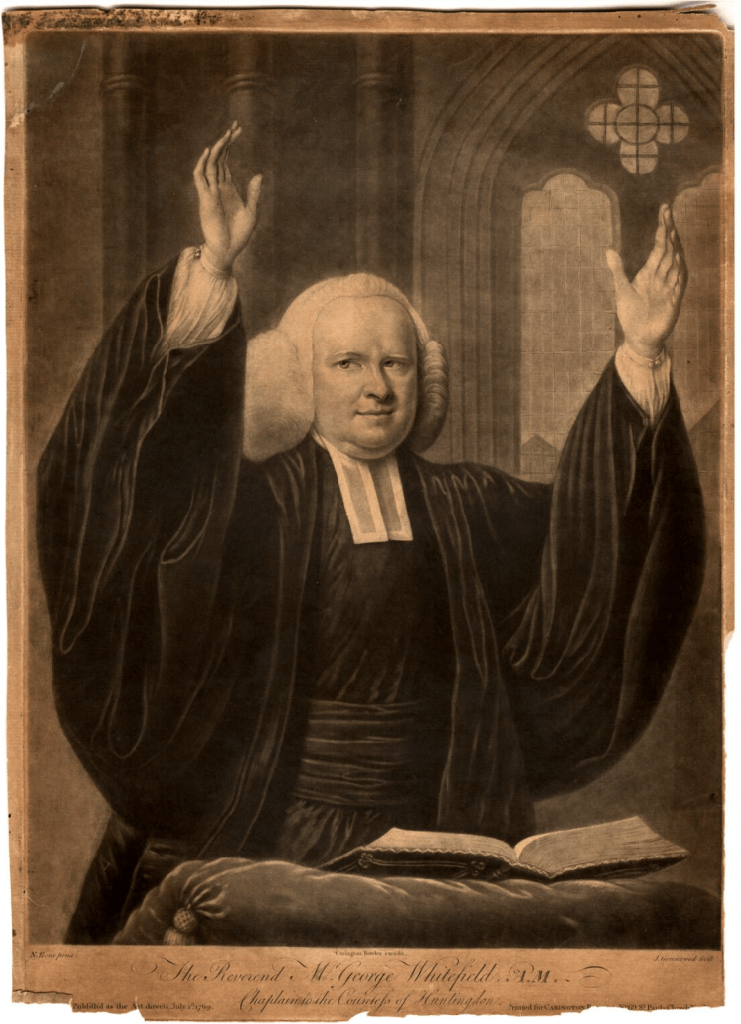

John Wesley and George Whitefield — Field, Fire, and Formality

No discussion of Protestant appearance can omit John Wesley (1703–1791) and George Whitefield (1714–1770). They bridged Anglican form with evangelical fervour, carrying the Gospel from pulpits to open fields.

- Wesley, though a Church of England priest, retained black clerical garb and white bands throughout life — a commitment to order amid revival. His Journal notes his unease with excessive informality:

“I advised all not to affect plainness to the contempt of decency.”

He saw dress as moral pedagogy: neatness, restraint, and propriety as reflections of sanctification. - Whitefield, his friend‑turned‑rival in method, preached under the open sky before tens of thousands, often still robed in his black academic gown. Benjamin Franklin’s portrait of him captures a worn velvet coat and clerical bands fluttering in wind — visual irony, a preacher of thunder dressed like a don.

Their robes rooted revivalism in Reformed discipline; emotion clothed in decency. The collar would later capture that same synthesis.

“Wesley and Whitefield wore the uniform of order while preaching the liberty of grace.”

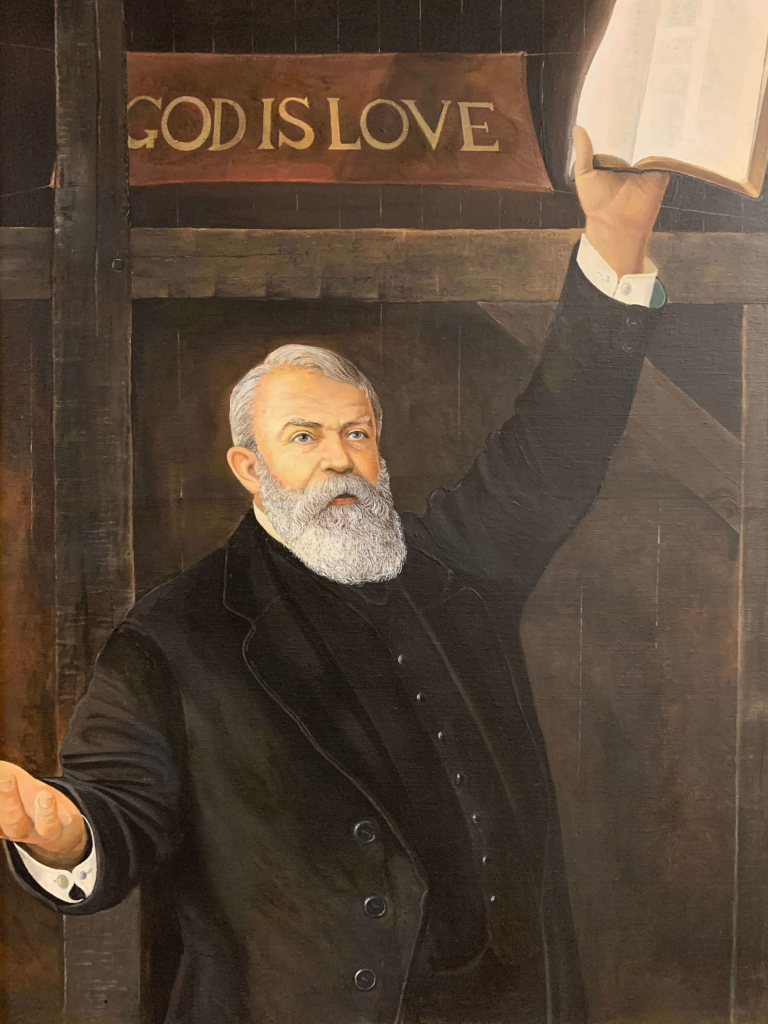

Charles Haddon Spurgeon — The Prince in a Plain Coat

Charles Haddon Spurgeon, the Baptist giant, never wore the modern clerical collar, but he was instantly recognizable in the streets of London. He preached and walked about in a black frock coat, black silk cravat tied in a bow, and often a velvet-trimmed overcoat. Contemporary illustrations and photographs show that this attire stood out dramatically against the browns and greys of working-class dress. Spurgeon himself saw the advantage, speaking to his students on posture, action and gestures, he remarks:

There is a wide range between the fop, curling and perfuming his locks, and permitting one’s hair to hang in matted masses like the mane of a wild beast. We should never advise you to practise postures before a glass, nor to imitate great divines, nor to ape the fine gentleman; but there is no need, on the other hand, to be vulgar or absurd. Postures and attitudes are merely a small part of the dress of a discourse, and it is not in dress that the substance of the matter lies: a man in fustian is “a man for a’ that,” and so a sermon which is oddly delivered may be a good sermon for all that; but still, as none of you would care to wear a pauper’s suit if you could procure better raiment, so you should not be so slovenly as to clothe truth like a mendicant when you might array her as a prince’s daughter.

He saw no contradiction between plainness and gravity.

“Cleanliness is next to godliness, and order is the first law of Heaven,” he quipped, half humour, half creed.

In the pulpit of the Metropolitan Tabernacle, Spurgeon’s apparel embodied Baptist Protestant respectability — the balance between Reformation restraint and Victorian decorum. His collar was not costume but conscience: a reminder that the preacher is set apart only by faithfulness, not fabric.

He stressed both humility and propriety:

- From Lectures to My Students (“The Minister’s Self‑Watch”): “The preacher should mind his attire so as not to dishonour his office; for though grace is better than garments, yet the Lord’s servant should not make righteousness ridiculous by slovenliness.”

- From a later talk recorded in John Ploughman’s Talks: “It is not clothing that makes the preacher, but decency and order adorn his doctrine.”

D. L. Moody — The Evangelist Without a Uniform

Across the Atlantic, Dwight Lyman Moody (1837–1899) represented the industrial‑age evangelist: business‑like, brisk, equipped for mass evangelism rather than parish life. Photographs often show him without a clerical collar, his beard untrimmed, coat plain, neck open. The absence itself was meaningful — a deliberate Protestantism freed from sacerdotal costume.

“I like the religion that walks into the factory and the workshop,” he once remarked, “not the one that stops in the sanctuary.”

Moody’s collarless ministry hinted at democratic Christianity — a new phase in the Reformation’s long suspicion of religious attire. Yet even here the chain was unbroken: he left space for conscience, not chaos.

From Geneva bands to open collars, the Reformed tradition had finished the circle — every generation re‑interpreting simplicity for its age.

The Birth of the Modern Collar

The clerical collar, as we see it today — a stiff, detachable white band encircling the neck — originated with the Scottish Presbyterian Rev. Dr. Donald McLeod of Glasgow around 1865. Scottish ministers, by then, commonly wore dark coats and white neckbands. McLeod’s innovation was to turn the white band around the neck entirely, leaving only a narrow white edge visible above the black waistcoat. Thus was born the “clerical collar” or “Roman collar,” though its creator was neither Roman nor ritualist.

An 1894 issue of The Church of Scotland Magazine noted wryly:

“The white collar now so familiar in the ministry had its earliest home among the Presbyterians of Scotland, and was intended as a symbol, not of sacerdotalism, but of decency and order.”

This seemingly small sartorial shift had profound symbolic resonance. The collar, by being enclosed and subdued, avoided the theatricality of Anglican surplices while maintaining an unmistakable professional dignity. It was the Protestant answer to the cassock’s pomp — sober, efficient, identifiably clerical, yet unpretentious.

Symbolism and Scripture: “A Servant’s Yoke”

Over time, the collar acquired a spiritual metaphor even among the Reformed: the white band resembled a yoke, symbolising servitude to Christ. This stood comfortably alongside Scripture:

“Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me… For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.”

(Matthew 11:29–30, KJV)

The irony is rich: an invention born in an anti-hierarchical movement ultimately produced a universal sign of religious vocation. What once distinguished the priest from the layman now became, for many Protestants, a mark of ministry rooted in service rather than status.

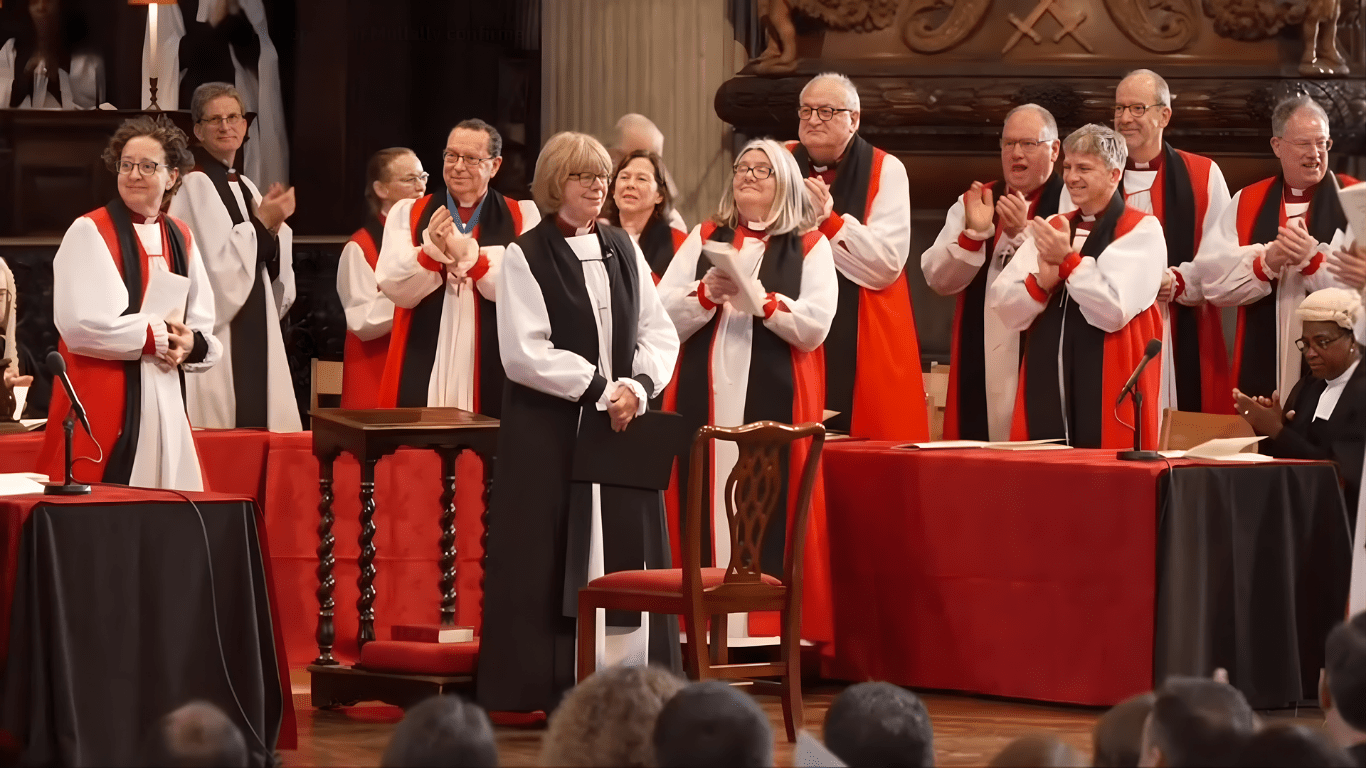

From Collar to Consistency: The Present Tension

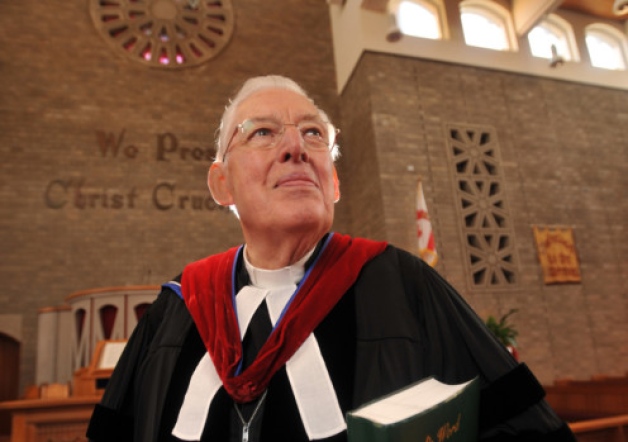

In the contemporary Reformed world, the collar evokes ambivalence. Some ministers cherish it as a visible reminder of spiritual calling. Others resist it, fearing a slide toward clericalism.

“The collar is a dog-collar in the best sense — it says ‘This sheepdog is on duty.’ In a hospital corridor or on the Underground, it opens conversations that would otherwise never begin,”.

One might recall Luther’s words once again:

“We are all consecrated priests through baptism.”

The collar, then, carries an ironic doubleness. It symbolises both the unity of the Christian calling and the enduring differentiation of vocation — an outward acknowledgment that some are called to serve visibly, that order itself is not vanity but stewardship.

As the Apostle Paul wrote:

“Let all things be done decently and in order.”

(1 Corinthians 14:40)

That text forms, perhaps, the truest motto for the collar’s survival in Reformed tradition.

The Witness of Visible Vocation

For all the Reformed wariness of outward show, the clerical collar, when worn with humility, serves as a quiet instrument of witness. Its white band, encircling the throat, may remind both minister and passer‑by that the mouth is consecrated to speak of Christ. In a secular age often indifferent to the Gospel, visible vocation offers silent testimony — the word preached before the word spoken.

God’s Word declares:

“A city that is set on an hill cannot be hid” (Matthew 5:14)

“Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven” (Matthew 5:16).

The collar, modest and unmistakable, may open doors that prejudice or fear would otherwise close, inviting questions, confessions, or counsel from souls in distress. As Paul wrote, “We are ambassadors for Christ, as though God did beseech you by us” (2 Corinthians 5:20); every ambassador wears some token of his commission. Thus, the collar can function not as a boundary but as a bridge — a visible pledge that faith walks openly in the world, not hidden away within its sanctuaries.

A Circle Closed

The journey of the clerical collar — from Lutheran rejection of ornament, to Genevan sobriety, to Presbyterian innovation — mirrors the evolving theology of public witness. It began as rebellion against vesture, became a token of scholarly gravitas, and ended as a quiet sign of vocational obedience.

The circular band of white at the neck thus tells an unlikely tale: of Reformation’s refusal to become chaos, of freedom disciplined by order, and of the continuing dialogue between inner faith and outward form.

As the psalmist wrote:

“Let thy priests be clothed with righteousness; and let thy saints shout for joy.”

(Psalm 132:9, KJV) And perhaps that, in the end, is the point.

It is not the fabric, but the faith beneath it, that matters.